Ming Tombs - Concubines

What is a concubine?

Concubines are women living in quasi-matrimonial relationships; they live together with a married man but to whom they are not formally married. Concubines normally enjoy a lower social status than the man or the official wife or wives.

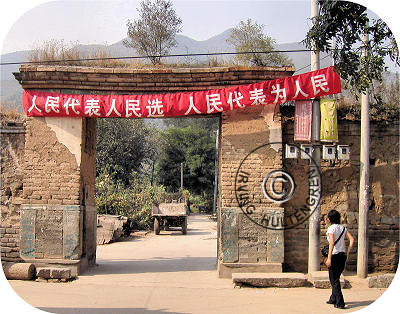

Entrance to Ming concubine mausoleum

Having one or more concubines was quite common in imperial China -that is, if one could afford it.

Concubinage is often snickered at but such attitude ignores that there were very few life options available for women in China's imperial days. With a few exceptions, a woman could become a wife, a maid, a concubine or a prostitute.

Concubinage was in many cases the only way that a poor woman could achieve financial- and social security if she could not find a husband. And however undesirable, concubinage was still vastly safer than prostitution and with a lot less chance of attracting STD.

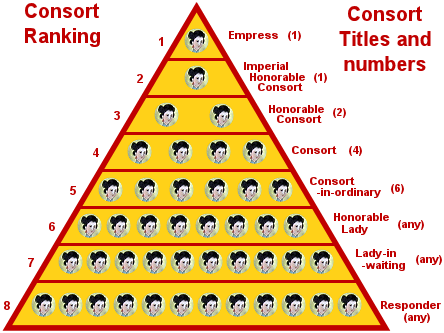

Imperial consort titles

Some Ming Consort Designations:

| Huang kuei-fei | ≈ | Imperial honored consort |

| Kuei-fei | ≈ | Honored consort |

| Hui-fei | ≈ | Gracious consort |

| Xian-fei | ≈ | Worthy consort |

| Shu-fei | ≈ | Pure consort |

| Kang-pin | ≈ | Wholesome consort |

But contrary to its predecessor dynasties, and its subsequent Qing dynasty for that matter, the Ming dynasty did not appear to have had well regulated concubine titles or rank order.

The main designations of consorts during Ming were fei, pin and fu-jen; prefixes would in turn allow for subdivisions, albeit not a ranking per se. See sidebar for Ming consort subdivisions as also the insert box giving details on the well-ordered consort ranking and designations of the subsequent Qing dynasty.

Qing Dynasty consort ranking (1644 - 1911)

A life in leisure?

Intrigues and bickering between concubines were rampant and ensured that daily life was far from a life of pleasant leisure.

The internal hierarchy was firm and inflexible and consorts would fiercely guard their unofficial ranking and do virtually anything to advance.

Spending a night with the emperor was hard to come by due to the high number of consorts available.

Even so, this was the best a consort could hope for since giving birth to an imperial offspring was the best, quickest and safest way to jump up high on the list.

Yellow dragons on blue

background was used

by a consort of rank 5

-Consort-in-Ordinary

In the later Qing dynasty (1644 - 1911), the ranking decided what a consort was entitled to. Her clothing, food, the color of bowls and plates, obligations, daily chores, and even her residence were all aligned with her status.

Green dragons on yellow

background was more

prestigious and used

by Honorable Consorts

-ranks 2 and 3

Empress

Whereas the Ming Emperor could have many consorts he would only have one empress. The mother of the Emperor would bear the title of empress dowager and his grandmother would be entitled grand empress dowager.

Becoming Empress was not a designation for life. On a few occasions the empress fell from favor and was demoted to a common consort. A typical reason for such demotion would be the failure to bear a son and heir.

How become an imperial consort?

Ministers, generals and officials offered their daughters as concubines to the court. If accepted as an imperial consort, the girl would at least lead a life of relative luxury compared to her sisters outside the Forbidden City.

Divorce an emperor?

Concubine Wen Xiu

The only consort known to have divorced an emperor in history is consort Wen Xiu, the last Qing Emperor Puyi's concubine.

She was expelled from the Forbidden City along with the emperor in 1924 and lived with him and his wife in Tianjin in the period 1924-31.

In 1931 she made the unusual demand of seeking and ultimately being granted a divorce from the now dethroned emperor -unprecedented for almost thirty centuries! He immediately issued an edict demoting her to a commoner.

She returned to Beijing and spent the rest of her life as a primary-school teacher. She died of illness in 1950 without ever remarrying.

Another way of becoming an imperial palace consort was as a gift from a foreign country, typically Mongolia and Korea.

If the consort of a Chinese family was promoted to the higher ranks then her family would be bestowed stipends or military ranks. If she made it to the highest ranks then her family would even be elevated to nobility. The latter was however made non-hereditary as per a decree in 1529 by the Ming Jiajing Emperor.

Leave the palace alive?

Becoming an imperial consort was not the same as a life sentence inasmuch as it was not impossible or even uncommon for a consort to return to her family.

While in the service of the palace no concubine was allowed to communicate with the outside world. Not in person and not even by mail.

This ban went so far as to not allow a doctor to enter the palace and see a sick, female palace patient. Her illness would be carefully described and prescriptions acquired and administered according to the doctor's advice.

Chang An Gong Palace in the Forbidden City, Beijing.

Built in 1420 and occupied by Ming and Qing consorts

But there were ways to leave the palace without your feet first. Just like the emperor could receive a consort as a gift from a foreign ruler, so could the emperor choose to present one of his concubines as a gift to a foreign ruler. It could however be argued that one prison had merely been replaced by another.

Some consorts were allowed to return to their families with an adequate pension after many years of meritorious service. The minimum period to serve was set at five years by the Hongwu Emperor in 1389.

Retired consorts were free to pursue a normal life, including marriage and establishing a family.

Many consorts too old to be of any further use for the imperial palace chose instead to become employed by the Imperial Laundry Service or pursue a life as a nun.

Consort Burial Sites

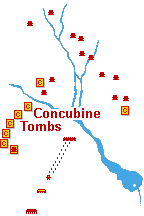

The Ming imperial consort tombs are located inside the imperial burial grounds of Shisanling north of Beijing along with the mausoleums of most Ming emperors. According to the official Ming Tombs web site there should be seven, excluding Siling, and I have been able to locate all seven albeit with some difficulty.

Click here to select the consort tombs from a map.

Most of the larger ones (marked ![]() on the map left) are located in the southwestern part of the overall area. Also Siling is found in this neighborhood.

on the map left) are located in the southwestern part of the overall area. Also Siling is found in this neighborhood.

Most of the sites are increasingly difficult to locate since the local farmers gradually have assimilated the burial sites into their cultivated land area and even dismantled the protecting tomb walls to use the excellent, large Ming bricks for own purposes.

Cabbage field around plinth ruins

The concubine tomb area at the top of this page is even completely enwalled but has even so long since been occupied by many farmers, who have built a small village complete with houses and streets within the cemetery walls. And they are using the tomb area itself for growing vegetables and corn (see picture with plinth ruins right).

Immolation

One of the less glamorous parts of concubinage was the fact that the consorts were considered personal "property" of the man. They were his to do with as he pleased, including taking them with him to the afterlife.

Ming concubine tombs assimilated by farmers

In many older tombs of nobles we find the remains of several females of similar or slightly lower age buried close to a single man, a strong indicator of concubinage.

The imperial consorts were either executed by palace eunuchs or chose to commit suicide, normally by hanging themselves with a silk scarf or by taking poison.

In the first part of the Ming dynasty concubines were often immolated and buried in separate tombs near the deceased emperor. In a few cases, consorts were buried alive in a standing position -awaiting the arrival of the emperor in the afterlife.

Of course, those consorts who made it to empress were granted the ultimate honor of being buried together with the emperor in his mausoleum.

Immolation was discontinued after 1464 when the Tianshun Emperor in his will declared the practice uncivilized.

Honorable Consort Tian's tomb, Siling

-also containing Ming Chongzhen Emperor

Exceptions

As an exception from all rules and practice, the last Ming Chongzhen Emperor was actually buried in the tomb of his favorite concubine and not the other way around.

In despair over having lost the empire, he committed suicide in Jingshan Park behind the Forbidden City on 25 April 1644. When the rebels found his body a few days later they unceremoniously dumped it in the already completed tomb for his consort. The Chongzhen Emperor still rests together with his beloved concubine, Honorable Consort Tian, in her tomb, Siling.

And while on exceptions, no concubines were buried with the 9th Ming Emperor Hongzhi since he was the only emperor who being a strict confucian never took a concubine.