Ming Consort tombs -Tomb 7

Tomb 7 in front of the Shisanling valley in the background

-the village left is trespassing the tomb area

Yongling Backdrop

This Ming concubine tomb number 7 is hugging the same mountain ridge as that of Deling, the mausoleum of the Tianqi Emperor (r. 1621 - 1627) and the last Emperor tomb made for an emperor. The next and last Ming Emperor was buried in his concubine's tomb, Siling.

This concubine tomb is within eyeshot of Yongling mausoleum, the final resting place of the Jiajing Emperor (r. 1522 - 1566), the 11th Ming "Son of Heaven". Deling cannot be seen from this consort tomb as it is hidden behind the mountain ridge, which they share.

Consort tomb 7 is in a sad state of repair like most of its sister Ming consort tombs. In fact, the tomb mound and the memorial stele are the only fully intact structures.

Section of front outer wall

incorporated into a farmer's yard

The overview photo above was shot from the back section of the perimeter wall, up the mountain ridge. The inner- and outer wall sections as well as the tomb mound are clearly visible. The trained eye will even spot the plinths.

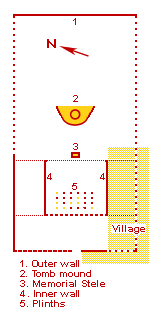

Blueprint

The tomb has three main sections; the front part, which presumably contained the ceremonial hall, the central part which contained the stele and tomb mound, and, furthest back, a steep incline up to the back part of the surrounding wall.

The mausoleum is almost orientated east-west, a little unusual considered the importance of fengshui, but likely dictated by the need to have the mountain ridge towards the rear. This would at least prevent evil spirits and harsh winter winds from bothering the occupants.

All traces of gates and doors have been lost.

The local farmers have intruded so heavily into the mausoleum area that large parts of the tomb structure have been removed or outright incorporated into the farmers yard walls and even houses.

Most of the original tomb area has been converted to an orchard. A large section between the southern inner-and outer walls has been developed into a full-fledged village.

Ruins of the rear outer wall

The plinths, which probably supported the pillars of the original ceremonial hall, have to some degree been moved around to accommodate irrigation of the crops grown inside the orchard.

The perimeter wall

Even though most of the perimeter wall has long since disappeared, enough sections remain as ruins to reconstruct the overall layout of consort tomb #7.

The rear wall and a large piece of the southern side wall are still extant. Also the base of the front wall is extant and a small section of the front wall has survived because the local farmer used it as his back wall.

Plaster intact on a section of the southern outer wall

The rear outer wall up the hillside has lost almost all of its plaster cover and now presents itself with the original, traditionally large brick of the imperial Ming era.

In contrast, the large extant piece of the southern side wall still carries some of the original red colored plaster. Nature is gradually taking its toll also on this wall section, although the largest danger for disappearance is the farmers' recycling of the ancient bricks for their own private use as evidenced all around consort tomb #6.

Base of front outer wall

The front section has long since been dismantled this way but enough remains of the base to establish with certainty the southern end of the mausoleum.

Piece of wall in farmers house

Interestingly, the farmers have completed removed even the base of the outer wall adjacent to the village houses so as to create an opening for farm vehicles to enter the orchard. But they left the last small bit, which now peaks out from the back wall of the farmer's house (see photo)!

Most of the southwestern area between the inner- and outer walls has been completely taken over by the local village.

The elevation on the left pointing right at the village shows

where the western outer wall once was

As a consequence virtually all of the western outer wall has been dismantled and replaced by farmhouses and yard fences.

How do we know that there indeed was a western outer wall? Because we can still trace a slight elevation in the ground perfectly aligned with where the wall used to be. Moreover, the location of the elevation is perfectly symmetric with the eastern outer wall, much of which is still extant.

Memorial stele

So where did the brick go? Most of them were used to build terraces up the hillside to accommodate irrigation and cultivation. But many other bricks were used as part of the walls of the farmers' houses.

Generally, the layout of consort Tomb #6 is pretty hard to figure out, because of the many missing pieces.

The memorial stele

The stele is some two meters tall, is in perfect condition -except for a crack in its base- and is easy to locate inside the orchard. In line with good geomancy, the stele is placed on the center line of the mausoleum area.

A row of pine trees right behind the stele form a serene backdrop and makes it stand out as a clear landmark.

The stele carries no inscriptions, as is also the case with the other memorial steles of the Ming dynasty.

The top part of the stele is decorated on both sides with two phoenixes, symbols of an imperial empress -or, in this case, concubines.

The birds are captured in flight among swirling clouds.

A large section of the northern side of the inner wall is extant

The inner wall

The inner wall still exists in part.

Whereas it is easy to identify the northern (left) side of the inner wall as it is mostly extant (see photo), then the southern (right) side needs a closer inspection.

At first glance, the southern side seems to be missing, but it has in fact been incorporated as rear walls of the adjacent farmers' residences.

Eastern inner wall intact

Farmers simply built their houses against the inner wall and luckily left the "outside" wall untouched (see photo).

Front inner wall base

Thus, the outside wall still carries part of the original plaster cover and the colors can even be clearly traced.

The front (western) section of the inner wall has been dismantled and by now only a row of the base remains. That is however enough to establish where the front wall was originally erected.

It is on the other hand hard to identify where the rear inner wall used to be. There is simply nothing at all left, not even some base stones.

Most likely the rear wall was a divider between the ceremonial hall area and the memorial stele, since the latter would normally be placed in the same secluded area as the tomb mound. The rear wall could possibly also have been built between the stele and the tomb mound.

Plinths

Sixteen plinths occupy an almost rectangular area inside the inner walls.

Plinths supporting the columns of the Ceremonial Hall

Also in this photo are inner wall (left), memorial steele,

tomb mound and rear outer wall

Tomb #6 would likely at construction time have contained a Ceremonial Hall surrounded and protected by the inner walls. The plinths found today would have constituted the base support for the wooden columns, which carried the entire structure.

The current location of the plinths is dubious. They bear signs of having been moved around somewhat from their original position in order to accommodate the cultivation of the crops now grown there.

Moreover, the stone foundation, which would have carried the weight of the plinths, columns, walls and roof, has long since disappeared and thus can not verify the plinth location.

The way the plinths are placed today indicate a Ceremonial Hall five bays wide and three bays deep. By any measure, that would have been an unusually large hall for a consort mausoleum -even for a favorite consort. In fact, that size would have been common for an emperor.

The truth is lost in the vast depth of history.

Tomb mound

Tomb mound with Yongling in the background

Contrary to the other consort tombs, the tomb mound of tomb #6 is not only extant but also in an extraordinary good condition.

The mound sits atop an elevated, almost semicircular base, which has played a significant role in preserving the mound itself. The other and earlier consort mounds have all mostly collapsed because they lacked a reinforced platform.

On a good day, the mound offers a magnificent view with Yongling ceremonial hall peaking above the tree line in the near distance (see photo).

Tomb mound of Consort tomb No. 7

The concrete, round top of the mound itself has ensured that it survived the tides of time better than all of its sisters.

Occupants?

I do not know who is laid to rest here. The state of the tomb mound and the construction of its base both point to a period towards the fall of the Ming since this way of building a consort mound was quite common already in the succeeding Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

A good guess as to occupant would be consort(s) of the Tianqi Emperor (r. 1621 - 1627) because of his late reign period and because of the proximity of consort tomb #6 to his mausoleum, Deling, just around the tip of the same mountain range.