Ming Tomb Layout

Out with the old – in with the new

Zhu Yuanzhang (right), the first emperor of the Ming Dynasty, not only left his footprint on China's history while he was alive.

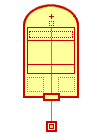

A traditional, square shaped

Han dynasty tomb in Xi'an

He also left his mark in death by setting completely new standards for layout of Chinese imperial tombs.

First, he introduced a round or oval tomb mound. This broke with the traditional square shape commonly used during the golden Han and Tang dynasties.

Walled courtyards

He also introduced walled courtyards in front of the tomb mound.

Last, but not least, the unwavering compliance with good, traditional Feng Shui, or geomancy, deviated from previous traditions.

Outer Sacred Way

Outer Sacred Way Xiaoling

Before arriving at the main tomb entrance one had to pass through an extended so-called Sacred Way. This was a multi-kilometer awe inspiring road lined with large stone sculptures and passing through various buildings, bridges and gates.

The Sacred Way served the purpose of paying tribute to the deceased as also to instill a sense of humbleness in the visitor. A separate web page covers the layout and contents of the Ming Sacred Ways in more detail.

Inner Sacred Way

Inner Sacred Way at Yongling

Each tomb also had its own internal Sacred Way. This was the straight line from the entrance of the mausoleum in the south all the way to the tomb mound in the north.

The line was paved with large rectangular slabs of stone or marble and marked the central north-south line through the entire tomb. This Inner Sacred Way is commonly resembled to the spine of a dragon. It was frequently flanked with "dragon scales" on both sides (see image from Yongling).

Where the inner Sacred Way met up with stairs leading to gates or halls the flight of stairs on the central line were always more immaculately decorated and larger than the parallel side stairs.

Deling outer wall

Only the emperor and the empress were permitted to walk or be carried on the Sacred Way. Others were relegated to use parallel gates, stairs or bridges.

The inner Sacred Way is easily spotted in all imperial tombs and nowadays all visitors may stroll through the mausoleum on the central line.

The Tomb Courtyards

Ming mausoleums had two or three courtyards in front of the tomb mound. They were protected by an outer eastern and western wall running the entire length of the tomb from south to north.

Courtyards were separated by east-west walls. To pass from one courtyard to another one had to go through special gates equipped with large, wooden doors.

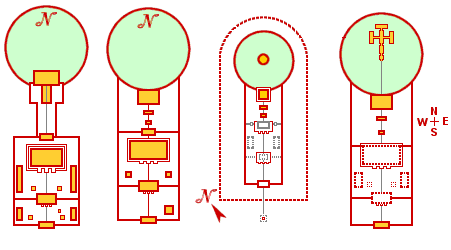

The four Ming tombs with three distinct courtyards:

(from left) Xiaoling, Changling, Yongling and Dingling.

In a few cases the gate was replaced by an imperial hall. This hall would be built on the dividing line itself with walls connecting the building to the outer eastern and western walls.

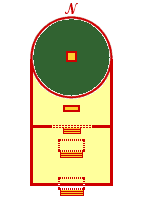

Three Courtyard Design

Only four Ming tombs boasted three courtyards: Xiaoling and Changling, the mausoleums of the 1st (Hongwu 1368-98) and 3rd (Yongle 1402-24) emperors as well as Yongling and Dingling, the mausoleums of the 11th (Jiajing 1566-66) and 13th (Wanli 1602-12) emperors.

The additional first courtyard –counting from the southern entrance- typically contains the Sacred Kitchen, tomb wells and a changing hall.

The changing hall was for the visiting emperor to change into special sacrificial robes.

600 year old Changing Hall Xiaoling

Sacrificial food was prepared in the Sacred Kitchen using pure water tapped from the internal water wells. This kitchen was not your ordinary small room with a stove. It was a large, square building with two or three wood fired cooking stoves, each with a cauldron with a two meter diameter or more.

Only the front courtyard of Xiaoling contained all the “proper” buildings; wells, changing hall and sacrificial kitchen. A later excavation also uncovered a sparrow tank (‘Quechi’).

The front yard of Changling only contains a pavilion added at least more than a century after the Yongle emperor’s death. Wells and the sacred kitchen were kept outside the mausoleum proper.

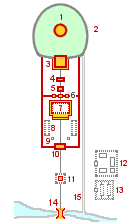

Deling

This last Ming tomb is an excellent example of how the standard layout developed during the dynasty.

The triple courtyard design had been abandoned forcing the Sacred Kitchen to be located outside and southeast of the main tomb in its own walled compound (#12).

The Changing Hall remained inside (#8).

The contents of the northern courtyard as a standard contained the Double-Pillar gate (#5) and the Sacred Stone Vessels (#4).

The subsequent Qing dynasty (1644-1911) by and large copied this latest design and applied it to most of its mausoleums.

The subsequent Qing dynasty by and large copied the Ming tomb layout but was far more regimented in terms of including all “prescribed” buildings, but that is another tale.

The Central Courtyard

The second yard contained the main sacrificial hall located on the central Sacred Way. It was the largest and most imposing building of the mausoleum. The hall was constructed on a triple layer platform with three flights of stairs on (at least) the southern and northern sides.

The southern, central flight of stairs up to the hall was decorated with a large, rectangular stone slate depicting a dragon (symbolizing the emperor) and a phoenix (symbolizing the empress) on a background of mountains and oceans.

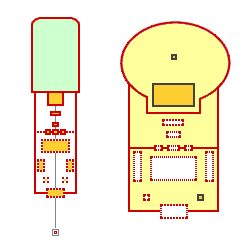

Jingling and Tailing

(not to scale)

The main rites venerating the tomb occupants were performed in the sacrificial hall. The hall contained the thrones of the deceased emperor and empress and often also their robes. The sacrificial meals would be served on large tables in front of the (empty) thrones.

Two side halls flanked the front of the sacrificial hall. The western side hall was used by the monks for reciting the ancient scriptures during the ceremony. The eastern side hall was used for storing the sacred scriptures and other ceremonial items between visits.

Note in Jingling (the Xuande emperor (5th)) and Tailing (the Hongzhi emperor (9th)) the two small, square constructions in the main courtyard. These are not Sacred Wells as in Xiaoling but ritual Silk Burners. The side halls in Tailing were somewhat unusually placed alongside the main hall.

Restored Double-Pillar gate

Changling, Shisanling

The Back Courtyard

This was the last enwalled area in front of the tomb mound itself. The contents differ a little but the most common structures found were the Double-Pillar Gate, the Sacrificial Stone Vessels and the Square City with the Soul Tower on top.

The Double-Pillar Gate was a purely symbolic gate demonstrating the importance of the tomb occupant. The five sacrificial stone vessels were placed on top of a large, rectangular solid stone slab.

Soul Tower of Changling

The Square City was a tall, square platform covered by dark gray brick on all sides. In most tombs a full width staircase of slanted stone would lead up to the base of the Square City and a flight of stones on both sides would lead further up to the top of the Square City.

In some of the Ming tombs a tunnel was cut through the base of the Square City leading to the wall surrounding the tomb mound.

On top of the Square City was the Soul Tower. This was a rectangular building containing in its center a tall stone tablet inscribed with the name of the tomb occupant. The tower had a double-eaved roof covered by yellow glazed tiles.

It is virtually always the Soul Tower, which is shown in books and tourist brochures, because it is the tallest and most prominent structure and the building that best survives the tides of times.

Siling Tomb Mound

Nobody was permitted into the back courtyard. Only eunuchs responsible for cleaning and other maintenance duties would enter this yard once the deceased emperor had been interred. And even they required a special entry permit from the reigning emperor.

The Tomb Mound

Furthest north was finally the tomb itself. The emperor and his wife or wives were buried in the tomb chamber deep underground and normally in the center of the tomb mound.

The chamber was covered by a colossal pile of earth kept in place by a surrounding dark gray brick wall. The shape of the earth mound was round or oval and, on a few occasions, an extended oval.

Some of the mounds are planted with trees, which symbolize continuation of the deceased.

Can I see the Burial Chamber?

Burial Chamber Dingling

Sure, but only in a few of the Ming tombs. Most of the Ming tombs have been left unopened and it is believed that only few have been robbed.

On punishment of death it was forbidden to go anywhere near the mausoleums. This “death zone” normally extended a mile or two in all directions –often all the way to the surrounding mountains.

Unfortunately, warlords broke into some tombs in troubled times in the first half of the 20th century. Most infamous is the desecration of the tomb of Empress Dowager Cixi, the “Dragon Lady” who ruled the empire from “behind the curtain” for decades in the late 1800s. This was however in the subsequent Qing dynasty.

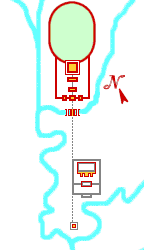

Xianling

Were they really all similar?

Certainly not. Especially three tombs stand out from the crowd.

Xianling, the tomb of the 4th Ming emperor Zhu Gaochi with reign name Hongxi (r. 1424-25), was on the emperor’s expressed wish kept rather simple. But it is not its smaller size that makes it unique; rather it is that the front courtyard and the back courtyard are placed some 100 meters apart and out of sight of each other.

This extraordinary layout is owed to the fact that local creeks and topography made it virtually impossible within a reasonable cost to construct a contiguous tomb in the location chosen by the emperor. By leaving the land unharmed the tomb was also in harmony with its environment.

Jingtailing

Also Jingtailing, the tomb of the 7th Ming Emperor Zhu Qiyu with reign name of Jingtai (r. 1449-57), differs from the rest by only having a layout normally allotted to an imperial Prince.

Jingtai was “demoted” by his brother, the 6th (and 8th) Ming emperor, to a Prince as a revenge for Zhu Qiyu having thrown him and his empress in house arrest for years. When the Jingtai Emperor died (with a little help?) not only did his brother have him buried in a simpler prince tomb, but the tomb was also located in Beijing’s western hills and not together with all the other Ming tombs north of Beijing. Jingtailing is hard to locate today as it is "buried" inside a retirement area for military personnel.

Siling

The last extraordinary imperial tomb layout is that of Siling, the final resting place of the 16th and last Ming emperor Zhu Youjian with reign title of Chongzhen (r. 1627-44).

This is the emperor, who hanged himself from a scholar tree on "Coal Hill" behind The Forbidden City.

Actually, Siling was the tomb of Chongzhen’s much beloved concubine, Lady Tian. The rebels who overthrew the Ming dynasty simply entombed the body of the hanged emperor with his concubine in total disrespect of Chinese customs.

It was a later Qing emperor who built an enclosing wall, a tomb mound, a small sacrificial palace and a memorial stele at Siling. Being a concubine tomb, Siling is also located far west of all the main imperial tombs although still in the same general mausoleum area of Shisanling. By the way, it is poorly marked and rather hard to find!