Zhu Zhanji - the Xuande Emperor

The Emperor has a rebel leader

roasted to death

Peace in the Empire

Born 1399 as Zhu Zhanji, eldest son of the Hongxi Emperor and Empress Zhang, Xuanzong ascended to the throne on February 8, 1426 with reign title of Xuande.

He successfully suppressed an early internal rebellion by an uncle after which he kept grip on power till his death in 1435. The rebel leader, his uncle Zhu Gaoxu, was strong as an ox and could lift the heavy bronze vessel under which he was being roasted to death for his betrayal.

The Emperor fought natural calamities, safeguarded the borders and patronized the arts. Supported by his mother, Empress Dowager Zhang, his 10 years of rule brought peace and prosperity to the empire.

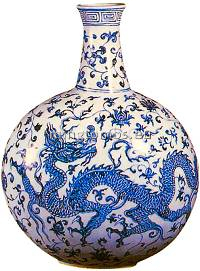

Ming porcelain

His first Empress Hu was childless and abdicated in 1425 in favor of second Empress Sun, who gave birth to two sons and two daughters. Both empresses survived the Emperor, who passed away 36 years old in 1435.

Chinese China from China

Himself being a competent poet and artist, the Emperor sponsored improvements in the manufacturing of ceramics, which led to the world famous Ming porcelain. He surrounded himself with precious articles such as luxury items, precious stones and unusual animals.

The Eunuchs Destroy the Empire

Whereas his uncle and his father wisely had eliminated all political influence by the palace eunuchs, the Xuande Emperor as part of his otherwise sound reforms made the monumental mistake of re-introducing power to the eunuchs. He established a palace school for eunuchs and even appointed them as military supervisors.

This unfortunately was the one reform that would prove to be the beginning of the end of the entire Ming dynasty, the last genuine Han Chinese imperial rule.

Already the Emperor's successor was hoodwinked by the eunuchs and as a consequence captured by enemy forces. In general, the eunuchs set out on a quest to rip off the empire and amass enormous wealth. Their secret society ensured that upright administrators or generals, who opposed them, would be slandered or blackmailed into submission.

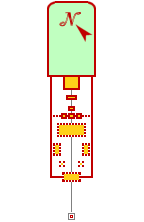

Jingling layout

Jingling, the Xuande Emperor's tomb, follows a standard Ming mausoleum layout.

In the ceremonial front yard behind the front gate was a ceremonial hall of the common 5x3 room size. The front yard also had eastern and western silk burners and side halls.

A triple-door gate led into the rear burial area, which is equipped with a Double-Pillar Gate, sacrificial vessels, a "Square City" and a memorial tower on top.

As always, the precious mound itself sits at the northern end of the mausoleum surrounded by a protecting stone wall, the Bao'cheng.

The mound itself has a rectangular shape with rounded northern corners.

The mausoleum lies mainly unrestored and is closed to the general public.

Tomb location:

Google Earth:

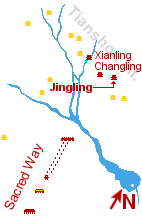

Jingling - the Third Tomb

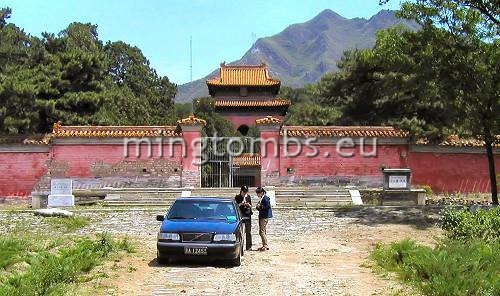

Front entrance of Jingling ("Scenic tomb")

Unsurprisingly, the Xuande Emperor for his mausoleum chose a site adjacent to and just east of his grandfather the Yongle Emperor's tomb, mirroring his own father's tomb just west thereof.

So already by the year 1435 the first three tombs around the Mount Tianshou site had occupied the "best" locations from a geomancy point of view; those of the Yongle Emperor, his son and his grandson.

The Front Gate

Following in the footsteps of his father, the Xuande Emperor ordered that his mausoleum be kept simple. It is nevertheless still considerably better equipped than that of his father.

The construction of Jingling (literally "Scenic Tomb") started in January 1435 and took almost 28 years to complete. It covers an area of about 25,000 square meters. It is located at the foot of the eastern peak of Mt. Tianshou.

Memorial Tablet

First, it has a traditional front entrance -well, maybe "had" would be more correct since the original structure is long gone. The stone foundation and the stone pillar bases remain in place so we know that the gate followed tradition being three rooms wide and two deep. The photo on this page shows that a newer wall has been erected to cover the gap between the original sidewalls -roughly between the two stone markers.

The Sacred Way looking north

The Sacred Way

Jingling is not accessible -not even for good words- but a photo straight up the center "Sacred Way" facing north still clearly shows the stone foundation of the sacrificial hall, the triple gate into the burial area, the stone sacrificial vessels (through the middle gate) and the memorial tower on top of the "Square City".

As with the front gate, the stone bases of the pillars carrying the roof of the sacrificial hall evidence that the original structure had five rooms across and three deep.

The hall foundation has three flights of stairs, the widest at the center of the Sacred Way.

Ruin of eastern silk burner

The walls separating the sacrificial and burial areas and connecting the outer walls to the triple gate have collapsed and the ruins removed. Otherwise, the gate itself has been restored.

Tell Tales

With a little effort it can be unveiled that the sacrificial front area of Jingling originally was equipped with eastern and western silk burners as well as with eastern and western side halls.

The side halls housed the tools and prayer plates for the sacrificial ceremonies.

Empress Sun

The sacrificial burners were used for burning prayer paper and gold and silver ingots made of paper at the conclusion of the sacrificial ceremonies.

The photo on this page shows the foundation of the eastern silk burner. The burner itself - a square stone construction covered with decorated tiles - is no longer there.

Occupants

Jingling has never been opened and has likely not been robbed. Other than the Emperor himself also Empress Sun (died in 1462) is buried in Jingling, but not so the 10 concubines who were immolated on the Emperor's death.

Empress Sun was a native of Zouxian County (today's Zouping County, Shandong Province). She entered the imperial palace as a teenage concubine but was promoted to concubine of first rank or "Noble Consort", when the Xuande emperor ascended the throne in 1425.

In 1427 she gave birth to a son, whom the Emperor made crown prince and Heir Apparent, the later Zhengtong Emperor. In 1428, the Emperor deposed the childless Empress Hu and promoted Empress Sun. She outlived the Emperor and died in 1462.

Ten concubines were immolated with the Xuande Emperor. The deposed Empress Hu was interred in Beijing's western hills, the traditional burial site of princes, consorts and princesses.