Zhu Yujiao - the Tianqi Emperor

Wei disturbs Tianqi with state affairs

15th at 15

When the Taichang Emperor died in late September 1620 after less than a month as emperor, his eldest son Zhu Yujiao acceded to the throne as the 15th Ming Emperor, Son of Heaven, on October 1, 1620.

Born 1605 as the son of Empress Wang, who had passed away already in 1619, Zhu Yujiao was barely 15 years old when he became emperor.

He took the reign title of Tianqi ("Opening [of a ruler's way] by Heaven") and temple title of Xizong ("Bright Ancestor").

The Chinese had a polite way of expressing emperor Zhu Yujiao's illiteracy:

"He did not have sufficient leisure to learn to write"

It was decreed to use the Tianqi reign name from 22 January 1621, the Lunar New Year.

Yet another cipher

Zhu Yujiao should never have been emperor. His academic skills were poor to the point of being entirely illiterate.

He grew up in his grandfather's intrigue filled court and was offered little attention since not he but Zhu Changlou, the Taichang Emperor, was the Heir Apparent. Not that it really bothered him because it gave him ample time to pursue the leisure activity most dear to his heart -carpentry.

As fate would have it Zhu Changlou died unexpectedly after ruling a mere 29 days and suddenly Zhu Yujiao found himself on the throne -in charge of the once so mighty Ming empire.

In his defense it should be mentioned that he was an incredibly skilled carpenter. He spent almost all his days creating beautifully crafted items in wood. Once at a workbench he engulfed himself completely in the task and took unkindly to interruptions.

Tyranny, secret service, torture and terror

So who ruled the empire? Well, Zhu Yujiao trusted his wet nurse Keshi and readily extended the trust further to her close friend, a eunuch by the name of Wei Zhongxian. And more so since the eunuch also had been the butler of his mother.

Statue of an official

Wei (1568-1627) exploited the trust to the extreme. He pacified the disinterested emperor by usually presenting him with important documents from the Grand Secretariats when he was submerged in his carpentry. The predictable outcome was that the Tianqi ESmperor quickly dispensed with affixing seals to anything so that he could return to his beloved woodwork.

Wei appointed officials loyal to him and terrorized the court and administration with his secret service. Taxes were ever-increasing and the administration soon ground to a complete halt.

After 4 years a group of reformers tried to reintroduce Confucian values but they failed and were tortured and killed along with some 700 of their supporters. The reign of terror now continued unchecked until the death of Zhu Yujiao in October 1627. His successor exiled Wei Zhongxian to Anhui province where he wisely committed suicide.

But the damage done was irrevocable. The emperor’s tacit consent to the huge suffering of his people convinced them that the Ming had lost the Mantle of Heaven and that it was time to replace the dynasty with one that had benevolent rulers, who could reign as true "Sons of Heaven".

Internal rebellions were rampant. It was now just a matter of time ...

Deling layout

Legend:

1. Precious Mound

2. Tomb mound

3. Soul tower

4. Sacrificial vessels

5. Double-pillar gate

6. Triple door gate

7. Sacrificial hall

8. Side halls

9. Sacrificial burners

10. Front gate

11. Memorial stele

12. Sacrificial kitchen

13. Officials' offices

14. Five arches bridge

15. Drainage canal

Despite Tianqi not standing out as an excellent regent, he was nevertheless alotted a well eqipped mausoleum.

Apart from the "standard" structures Deling had a 5-arches bridge, officials' quarters, a sacrificial kitchen compound, side halls and a separate and additional "Precious Top".

The kitchen and officials' quarter are long gone and the area taken over by the local farmers.

Also the silk burners and the two side halls have gone into misrepair and been removed.

The main gate has been rebuilt but not with the original hip and gable roof.

The soul tower has been extremely well restored as has the wall surrounding the tomb mound.

Ling'endian -the main sacrficial hall- lies mosrtly in ruins and bears marking of fire.

The wall separating the sacrificial area from the burial area has been rebuilt as have the triple gates in its center.

Sadly, the mausoleum is closed to the general public.

Tomb location:

Google Earth:

Deling - Vessels, Double-Pillar Gate and Triple Gate

The last Ming tomb

The Tianqi emperor's mausoleum was named Deling and was the last imperial tomb built by the Ming at Tianshou Mountains.

[The subsequent 16th and last Ming emperor was buried in his concubine's tomb and the tomb built by the Qing].

Deling is located at the western foot of Tanyuling ("Pool-Ravine Ridge") of Tianshou Mountain. It covers an area of 31,000 square meters, a standard size for a Ming emperor, who had achieved little during his reign.

Zhu Yujiao did not take any personal interest in his tomb so construction only commenced after he had passed away after a mere 7 year rule at age 23 -more precisely September 1627. The last structures were completed five years later in 1632.

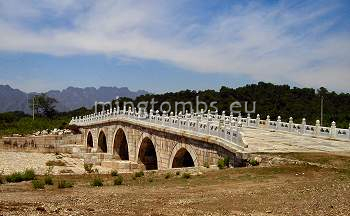

Five arches bridge

Directions

When coming from Beijing, Deling is geographically the first tomb that you meet. However, most tourists prefer to stay on the main road and visit one of the three open and famous tombs a little further up the valley road.

Once you pass the Dragon- and Phoenix Gate at the end of the Sacred Way and have crossed over the narrow, seven-span bridge you soon arrive at an intersection. Continuing straight would take you to Changling, so instead turn right and follow the winding country road until you enter a village.

Stele in front of the mausoleum

Take the first road on your right; a contemporary stone column in this T-intersection makes it easy to recognize. Follow this small, hilly and winding road until you come to a bridge. You will have passed Yongling on your left shortly before arriving at the bridge.

In fact, Deling is the southernmost mausoleum around the Tianshou Mountain. It is located east of Yongling, the tomb of emperor Jiajing, the 11th Ming ruler.

The five-arch bridge in front of you is the first part of Deling mausoleum. You can choose to drive across, but if you truly wish to savior the splendor and serenity of an isolated and majestic Ming tomb then I suggest that you seize the opportunity to walk across.

Stele and front gate

On the other side of the bridge a gentle slope leads up to the stele in front of the mausoleum.

The stele is in a good condition and well preserved. It rests on a square platform with a flight of six stone steps on all four sides. There is no signs of a earlier building around the stele.

Front gate in a snow storm

Further up the road comes a large stone platform accessed by a slope of slanted stones in almost the entire length on the front side. An additional staircase is located on either side. Use the side staircases in the winter as the slanted stones are too slippery and your shoes cannot get purchase (see picture).

The front gate -Ling'enmen or "Gate of Heavenly Favor"- sits on top of yet another platform accessed from the lower platform by a staircase divided into three sections on the front side.

The front gate itself is a standard 3 by 2-room building, with an ordinary roof covered with yellow glazed tiles. The original building is long gone and the current construction is a restored replica. The three doors are kept in their natural state. Note that the center door -reserved for the bodies of the emperor and empress- is taller than its sisters.

Ling'enmen - inside of the front gate

Also the stairs on the inside span the entire length of the gate and are divided into three equally large sections.

The recent major restoration from March 2002 to July 2004 also included the wall surrounding the tomb. Even so, the vermilion colored paint now needs a couple of touch-ups.

The imperial yellow glazed tiles decorate the top of the wall in its entire length. The crenellated wall around the tomb mound itself is kept in the original gray color.

Standard layout, or ...?

The basic layout of Deling reflects many years of refinement and fine-tuning of tombs by the Ming. And on face value this mausoleum appears to follow contemporary design standards, albeit at a somewhat smaller scale than most other Ming tombs.

Marble block -the dragon caught the pearl !

There are a few interesting twists though. Apart from the recent restoration Deling can indeed boast of some "specials" not found in earlier Ming tombs.

First is the orientation itself. Contrary to most Ming tombs, which in line with good fengshui are constructed as close to a south-north axis as possible and always facing south, Deling lies on an almost perfect east-west line and faces west.

Second is the five-arch bridge mentioned above. Other Ming mausoleum in Shisanling are equipped with a bridge in front of the memorial stele, but not of the scale and splendor as that of Deling.

Third, the loving small detail buried in the marble block in the center of the staricase leading up to the Sacrificial Hall. The block contains the usual carving of a dragon and a phoenix chasing a pearl high above mountains and water. But here for the first time the dragon has actually caught the pearl.

Ruins of Ling'endian

Furthermore, over time Ming had perfected drainage systems around and within their tombs; small drainage canals led water from the front and rear parts of the mausoleum down to the river along both sides of the mausoleum. The subsequent Qing dynasty took this skill to a much higher level.

The front courtyard

Inside the front gate is a wider than usual courtyard containing the main sacrificial hall -Ling'endian, or "Hall of Heavenly Favor". the courtyard is paved with stones, but weeds are gradually having the better of the surface.

Triple gate looking out (west)

Ling'endian was a standard 5 by 3-room structure covered with a double-eave hip and gable roof. At this time only the rear and left walls remain and they are quite dilapidated.There are no traces of the roof or the tiles covering the roof.

The remains of the pillars are however still visible on the part of the back and side walls that are still standing. The front part with the doors is long gone although the plinths clearly show where the bearing wooden columns used to be.

When the mausoleum was completed in 1632 there were two relatively large side halls used for changing clothes and to hold the tools used in the sacrificial rites. These structures are long gone but their platform stone outline can still be traced on the ground with a little patience.

Soul Tower with crenellated wall

Also the two silk burners have long since fallen apart, but also their stone foundation can still be seen on the ground.

The wall separating the front, sacrificial area from the rear burial area has been reconstructed and painted in the imperial vermillion color. The triple gates in its center have been rebuilt although the emperor shall no longer pass through the center one otherwise reserved for his exclusive use.

The back courtyard

The burial area was equipped with the traditional Lingxingmen, or Double Pillar Gate.

The wooden doors are long gone, but the marble pillars with their kylins on top still stand tall and majestic. Note that these kylins have an upwards curling bushy tail, which is different from all other Ming toms and the Sacred Way, where the kylins have no tail.

The kylins were Chinese legendary animals associated with peace and happiness.

Bhuddist symbols on a Ming stele

Also the traditional stone altar with its standard five ritual vessels, the incense burner, the candle holders and the vases survived the tides of time. See the photo higher up.

The Minglou, or Soul Tower, has been restored and now presents itself close to its original splendor. The tower on top of the "Square City" has an opening in each side and a double-eave hip and gable roof covered with yellow glazed tiles.

An inappropriate decoration

The stele inside the tower names the tomb occupant by his temple name, emperor Xicong. Nothing improper about that.

The "Crescent City"

But a second look at the stone base foundation uncovers a highly inappropriate decoration. Whereas the top section shows dancing dragons the bottom section has a number of Bhuddist symbols.

However much the emperor may have believed in Bhuddism in his life, religion never had any part of the Ming mausolea layout, decorations, buildings or burials.

The crenellated wall that surrounds the tomb mound connects with the Soul Tower creating the famous "Crescent City " between the tomb mound wall and the Soul Tower -named this way because it has the shape of a crescent when viewed from above.

Only three of the thirteen Shisanling Ming tombs have such a Crescent City, in Chinese yă bā yuàn. They are Zhaoling, Qingling and Deling.

The wall has been restored and where necessary totally rebuilt. Its overall shape is an extended oval. This part of the wall has been kept in its natural gray color.

The additional tomb mound

The tomb mound itself adds yet another uniqueness compared to most other Ming tombs.

Normally the tomb mound of Ming mausoleums has a slight convex shape and is bare save for being overgrown by trees and other vegetation. At Deling however an additional, large "Precious Top" has been added on top of and in the center of the earth mound. It is a circular earth-filled mound supported by a brick wall.

Outside and Southeast of the front gate used to be two distinct and separate walled compounds. The northern one was the sacrificial kitchen containing two store houses, a divine kitchen and a slaughter house. The southern compound was the ceremonial offices containing an office and a resting room for officials.

These compounds are long gone and the farmers have reclaimed them for growing crops.

Tomb occupants

The Tianqi Emperor was entombed in Deling in 1627 and was joined by his empress Zhang in 1644, 18 years later.

A native of Xiangfu County (today's Kaifeng, Hebei Province), Empress Zhang was born in 1606 as Zhang Yan to father Zhang Guoji, Marquis of Taikang. The name of her mother is unrecorded.

She was chosen as primary spouse and Empress in 1621 when Zhu Yujiao was enthroned. She outlived the Emperor as a dowager and stayed around the court of the succeeding Chongzhen emperor (reign 1627-1644).

After the death of her husband in September 1627 she was bestowed the honorary title of Empress Yi'an by Zhu Youjian, the Chongzhen Emperor and brother to her deceased husband, because she foiled a plot to have him bypassed to the throne. She was posthumanly honored as Empress Xiao'aizhe in 1645.

She lived in unusually interesting times. She experienced how internal rebellions against her husband's dynasty brought the empire to its knees losing control of all but a central army support. She saw how lies, deceit and intrigue stripped the regime of its best generals, who could have saved it. Instead, the unexpected enemy, the Qing from Manchuria, was allowed to cross The Great Wall and ultimately topple the Ming.

Empress Zhang however feared the internal rebels more and when Li Zicheng in charge of a peasant Chinese army attacked Beijing in 1644 she hanged herself with a silk scarf in The Forbidden City.

She was buried the same year in Deling. The succeeding Qing portrayed itself as a natural dynastic follower as well as a protector of Chinese culture and history and hence ensured that the Empress was interred according to prescribed rituals.