Zhu Zaihou - the Longqing Emperor

Longqing throws a banquet for Pahannachi

Six Years of Luxury ...

Born 4 February 1537 as the eldest surviving son of the Jiajing Emperor, Zhu Zaihou ascended the throne in February 1567, 30 years old, reigning as the Longqing Emperor. He died July 1572 after a reign of only 5½ years.

He was far from his father's favorite successor but the rule of primogeniture (that is, the eldest surviving son becomes Heir Apparent) prevailed giving Zhu Zaihou a shot at ruling China.

Only Zhu Zaihou's elder brother had been raised as Heir Apparent including how to handle state affairs, but he died unexpectedly. Zhu Zaihou was therefore ill prepared to assume the role of Son of Heaven and nor did he have much interest in same, for that matter. Instead, he took advantage of the opportunity to do whatever he wanted and chose a life of luxury.

... with an OK Outcome

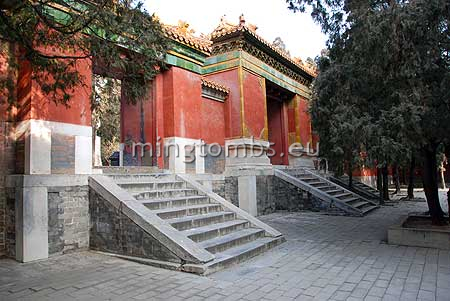

Doorframe detail in The Forbidden City

Although being weak and not involving himself in court affairs the Emperor at least chose some talented ministers and empowered them to steer the empire back on a better course.

They managed to expel from the palace the Daoists, who had been permitted to dominate court affairs under the Jiajing Emperor. They also brought the coastal piracy by Japanese bandits under control and rehabilitated unjustly punished officials.

But they unfortunately fell short on curtailing the massive corruption by the ruling class so at the end of the day the empire as a whole continued its slide towards self-destruction.

The Mongols are Appeased

The biggest feat however was that this weak and disinterested emperor actually achieved something that his predecessors had never managed to do; he established a peaceful co-existence with the enemy in the north, the Mongols.

Decoration detail, slaughter house of Zhaoling

Here is the story: Anda Khan, supreme ruler of the Mongols, promised the hand of the fiancée of his grandson, Pahannachi, to another man. Pahannachi got furious and fled south to the Ming court, archenemies of the Mongols.

Considering that the Mongols constantly raided northern China at will it would have been expected that the Ming in revenge would have executed a grandson of the Khan without further ado.

But prone to luxury and with no appreciation of "normal" state affairs the Longqing Emperor instead threw a grand banquet in the honor of Pahannachi.

When Anda Khan learned about the warm welcome of his grandson he ordered his troops to cease their raids of China and reinstated the prosperous trade in silk and horses with the Chinese.

In this way the Longqing Emperor without really trying managed to appease the Mongols and as a result created a window of opportunity to consolidate the northern defenses.

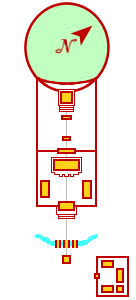

Zhaoling layout

Zhaoling was chosen as the first Ming tomb to be restored and opened to the public.

The restoration was intended to get as close as possible to the original design. Most of the standard buildings and constructions found in Ming tombs are indeed there, which makes for a rewarding visit.

Even the sacrificial kitchen compound southeast of the outer wall has been rebuilt, but it is unfortunately not open to the public.

The memorial tower greets the visitor in front of the tomb and behind it is a triple arch bridge spanning a small river.

The ramps in front of the front gate is larger than in most Ming tombs.

The ceremonial hall is also well restored and displays a brilliant example of the meals prepared for paying tribute to the tomb occupant.

The Soul Tower boasts an unusually wide and steep front ramp. Note the cracked stele inside the tower.

Behind the Soul Tower Zhaoling demonstrates a good sample of a "Crescent City".

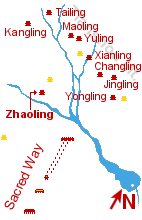

Tomb location:

Google Earth:

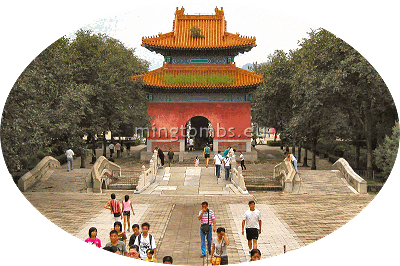

Panoramic view of Zhaoling

The Grandparents' Tomb

Zhu Zaihou was buried in Zhaoling (昭陵 or "Bright Tomb"), located at the eastern foot of Mt. Dayu ("Big Ravine"), a few kilometers south of Changling, the first Ming tomb at the Tianshou mountain range.

The burial chamber was actually built already in January 1539 by Zhu Zaihou's father, the Jiajing Emperor. He had intended to use it as a mausoleum for his parents but later abandoned the idea and left the tomb unfinished.

An imperial edict of July 1572 reinstated the tomb as a burial chamber for the recently deceased Longqing Emperor. Construction of the remaining structures was completed in 1573.

Not counting the Sacred Kitchen compound the tomb covers an area of 34,600 square meters. This would make it a middle-sized tomb in Ming mausoleum terms.

Restored Treasure Trove

Merit and Virtue Pavilion and Mt. Dayu

Like many other Ming tombs Zhaoling suffered badly from willful destruction during the transition from the Ming to the Qing dynasty in 1644. The Qing Qianlong Emperor had many of the structures restored or rebuilt during 1785-87, but generally somewhat smaller and hence not true to the original design.

Apart from minor maintenance jobs, the mausoleum gradually fell into disrepair until 1987 when the Office of Shishanling in Changping County decided to restore the entire tomb complex.

The comprehensive overhaul was completed in 1990 and the tomb opened to the public in the same year.

One of the two key objectives with the restoration was to promote tourism so visitors are very welcome.

The Sacred Kitchen compound outside Zhaoling

Zhaoling underwent yet another facelift in 2006-07 in preparation for the expected large number of visitors around the Olympic Games in August 2008.

The mausoleum compass positioning does not conform to perfect geomancy. Optimally the Sacred Way should run north to south down the center line but Zhaoling has been built on a northwest-southeast axis.

The Kitchen Compound

The Sacred Kitchen is located a little southeast of the tomb proper. It is a walled compound consisting of four buildings; the slaughterhouse, the sacred kitchen and two sacred warehouses.

Sacred Kitchen Slaughterhouse

The animals providing the ritual meat for the rites were slaughtered and cooked in the small pavilion in the southeast corner of the compound.

The slaughterhouse is easy to identify; it is the only square building in the kitchen compound as also the only one with a double eave roof. It's on the far right and rear on the photo.

The food and individual dishes were prepared in the Sacred Kitchen, the largest structure in the compound located against the eastern wall and in extension of the slaughterhouse

The two warehouses were used to store utensils and other items necessary for the preparation of the food stuff.

The main sacrificial hall inside Zhaoling displays a sampling of the many food dishes, which were prescribed as part of the fixed ritual.

Nowadays the kitchen compound is used by the tomb administration offices and by a company which sells little trinkets to tourists.

Stele and Bridge

Commencing the Sacred Way of Zhaoling and the first structure to greet the visitors is the Merit and Virtue Pavilion. It is a square building with a double-eave, top raised roof covered by yellow glazed ceramic tiles. The pavilion is erected on a square platform with stairs on all four sides; the additional platform augments the imposing impression.

Triple arch bridge and stele pavilion

The pavilion houses a stele mounted in a marble tortoise shaped animal with a dragon head. The stele signifies the meritorious deeds and lofty moral integrity of the tomb occupant, but true to Ming tradition the stele carries no inscriptions.

Despite the recent 1987 restoration efforts grass is already peeking through the roof tiles; a small bush even decorates the upper roof on the northern side.

Just behind (“north” of) the pavilion is a triple arch stone bridge lined with balustrades. It spans a small river the purpose of which is to prevent essential “qi” (divine power?) from escaping the mausoleum.

The inner Sacred Way runs across the center span of the bridge and continues up to the front gate.

Front Gate

Ling'enmen on a cold winter morning 2008

Zhaoling layout follows the double courtyard design; the front (south most) one contains the Gate of Eminent Favor, two side halls and the all-important main sacrificial hall. According to tradition it should also have held two silk ovens; they were undoubtedly there at the time of original construction in 1572 but all trace of them are now lost.

The front gate, Gate of Eminent Favor or Ling’enmen in Pinyin transliteration, is a 3x2 bay structure with a single eave roof. The current structure was overhauled as late as 2006-07. The gate is the only entrance to the mausoleum.

Eastern side hall

To reach the gate the visitor must scale not one but three platforms. First, a large flat elevated terrace leading up to a steep, wide ramp with slanted stones upon which yet another platform with stone steps in the entire building length hosts the gate itself.

Special, additional stairs have been built in the middle of the steep ramp to protect the original ramp and to ease ascend and descend by the visitors.

South Courtyard

Passing through the front gate one enters the ceremonial section of the tomb. This is the area where the filial duty was carried out on the anniversaries.

The side halls were used by the emperor and empress to change into their ceremonial robes and to store the various articles needed for the ceremonies. Nowadays, the halls offer an exhibition depicting the history of Zhaoling and of the tomb occupant, Zhu Zaihou –the Longqing Emperor.

Sacrificial Hall

The side halls are single eave structures set on a low platform. The halls are five bays long and one bay deep (not counting the roof overhang) –large for a Ming mausoleum. They are in excellent condition and are obviously recent renovations.

Throne in

ceremonial hall

But the overall imposing structure of the courtyard is undoubtedly the large Hall of Eminent Favor or Ling’endian. The Chinese name of the building is displayed on a plaque above the center door between the two eaves.

The building is erected on a large stone platform protruding in the front and with 5 sets of stairs; three to the south and one on each side. The larger, center staircase has a traditional Danbi stone decorated with mountains and clouds; the usual playful dragon and phoenix motif is conspicuously absent.

The staircases as well as the entire platform are all lined with new, marble balustrades.

This newly repainted hall structure is five bays wide and three bays deep. It has a double eave, hip and gable roof covered with the traditional yellow glazed tiles. As always, the combination of the imperial vermilion walls and yellow roof tiles separated by deep green and blue painted wooden bands with inlaid gold leaves renders a marvelous impression.

Sample ceremonial dishes

The hall has no windows but daylight enters the building through the south facing wooden lattice walls. The other three walls are solid and without any openings.

The back of the hall are occupied by four rooms with walls of lattice woodwork. In the center of each is an elevated throne belonging to the tomb occupant. It has a yellow curtain in front.

It was believed that the tomb occupants, in this case the emperor and his three empresses, would be present in spirit in these rooms during the sacrificial ceremonies. They may not physically have devoured the food, but it was believed that they would absorb the energy of the food.

For the benefit of the visitors building management has exhibited a sampling of the countless number of dishes that were prepared and served in the hall as part of the ceremony.

(South) Triple Gate between the two courtyards

Behind the tables are the four thrones of the tomb occupants.

Various articles used during the ceremonies in Ming times are exhibited along the sides of the hall.

The hall was built 1572-73, but was destroyed by fire in an electric storm in 1695. The Qing Qianlong Emperor had the hall rebuilt on a smaller scale in 1785-87, but it later collapsed due to inclement weather and lack of maintenance. The current structure was erected 1988-89 by the Chinese Ministry of Culture.

Note well that the eastern and western silk burners or Shenbo ovens are absent. They were without question part of the original structures since they played an essential role in the rites. For instance, the visiting family members would make sure to burn cards with their names in the ovens so that the spirit of the dead would bestow favors upon them in return for having paid tribute.

North Courtyard

Double Pillar Gate

The inner Triple Gate is the only passageway between the two courtyards. The burial (north) courtyard is elevated above the ceremonial courtyard so the Triple Gate openings have steep stone stairs leading up to them.

These gates are merely openings in the dividing wall, beautifully decorated however with green and yellow colored tiles and yellow glazed tiled roofs. The center opening is larger than its sisters and is for the exclusive use by the (deceased) emperor and empress.

Just inside the Triple Gate and spanning the Sacred Way is the restored Lingxingmen or the Double Pillar Gate. The wooden doors are kept in a red tinted color; in other mausolea the doors are painted in a more natural brown tone.

Sacrificial stone vessels

The stone threshold of this gate is intact and in good shape. This is rather important since it was believed that evil spirits could only travel in straight lines. One of the all-critical purposes of this gate was therefore to block these spirits from reaching the tomb mound traveling up the Sacred Way.

Another 40-50 meters north are the five sacrificial stone vessels on the altar. The latter carries various chiseled decorations like flowers and swirling patterns. The vessels symbolize an incense burner (center), two candleholders -right and left of the incense burner- and a flower vase at each end.

Stone ruins

In the center of the incense burner decoration is a coiled dragon with its head protruding towards the observer.

On both sides of the sacrificial stone vessels are remains of some stone structures. These are not found in any other Ming mausoleum and it's unknown what their role or purpose is.

Cypress trees are poking up through the stone ruins and the unwary visitor will not realize that the square stone protection around the root of the trees are there to protect the stone ruins rather than the trees.

Square City and Soul Tower

Behind the vessels is the so-called "Square City" - a large, tall square platform topped with a crenellated wall. A massive, steep and wide ramp topped with slanted brick lead from the courtyard up to the platform.

A narrow platform runs alongside the base of the Square City all the way on each side to the outer tomb wall.

Soul Tower on the Square City

A band of lighter stone around the base of the Square City carries some great decorations, but eager to reach the top few visitors pause to marvel at them.

On the left (western) side of the Square City is a steep flight of stairs leading up to the top. There is no means of getting to the top of the Square City on the right (eastern) side. See the photo on this page.

An arched tunnel through the center of the Square City opens up to a small yard. At each end of the yard is a steep ramp up to the top of the Square City. On the wall directly in front of the tunnel is a plate made of ceramic tiles. The plate presumably protects the tomb entrance.

Western stairs

On top of the Square City is another platform with the Minglou or Soul Tower, a square building having arched openings on all four sides, the ones north and south however blind. The platform has stairs on all four sides, also the blind ones. The tower has a double eave, hip and gable roof.

Bao Cheng

Inside the tower is a stele with the inscription "The mausoleum of Emperor Muzong". Muzong ("reverent ancestor") was the Longqing Emperor's temple name.

The stele is a rather unique specimen. The tower was burned down during the peasant uprising in 1644. The fire caused the very visible cracks in the stele. Adding insult to injury, shortly after being burnt the soul tower was struck and damaged further by lightning.

Damaged stele

The tower was reconstructed in the Qing dynasty during 1785-87 but not respecting the design rules of the Ming dynasty. Today’s tower is a more recent reconstruction closer to the original.

Topographically the tower has a good elevation offering a great view of a large part of the entire Shisanling valley.

Tomb Mound and Mutes' Yard

The tomb mound, or Bao Cheng in Pinyin, is almost circular and surrounded by a crenellated wall. Compared to all previous Ming tombs the earth filling, which protects the underground tomb, is higher and thicker.

As a consequence a gently curved wall was built to prevent the massive earth mound to link up directly to and apply pressure on the Square City. This extra wall creates the small courtyard between the mound and Square City mentioned earlier.

This yard –in Pinyin called yă bā yuàn- has many nicknames. One of these is “Mutes’ Yard” referring to the workers who constructed the tomb and its access tunnel, which presumably begins in this yard (but probably does not). They were allegedly mute so that they could not speak out the precise location of the tomb entrance.

Crescent City -note the curved walls

Another nickname is “yard of the dumb”; allegedly only the dumbest of all the workers were used for the construction of the final parts of the tomb entrance and they would be too stupid to remember and reveal the secrets.

Dingling seen from Zhaoling

The courtyard is also more officially called the “Crescent City”. This stems from the shape of its two curved walls; seen from above they appear to form a crescent shape.

The tomb mound has an additional mound in its center. This is purely symbolic inasmuch as the underground chambers are 15-20 meters below the surface.

Behind (north) the encircling wall is yet another, lower wall. Presumably, the objective with this additional wall was to protect the main wall from landslides and falling rock from the hill. The area between the two walls has an excellent drainage system built in.

Merit pavilion

as seen from the gate

Due to its somewhat isolated location a stroll on the crenellated walkway around the tomb mound is highly recommended. The quietness normally prevailing here offers a better opportunity to savior the serenity of the place. After all, this is a mausoleum and a Chinese emperor rests with his empresses deep down under the mound.

From the eastern side of the walkway is a splendid view of the entire neighboring Dingling mausoleum. From the northeastern side one can spot the remnants of the rarely visited concubine tombs located in the hills between Zhaoling and Dingling.

Tomb Occupants

Along in the burial chamber with the Longqing Emperor are his three wives: Empress Li (died 1558), empress Chen (died 1596) and Empress Dowager Xiao Ding (died 1614). The first died early, the second was childless and the third gave him the offspring he wanted.

Empress Xiao Yi

Empress Xiao Yi (family name Li) was born in Beijing to father Li Ming, Count of Deping, but mother unknown and year of birth not recorded. She was given the title of princess in 1553 but died already in 1558 and was buried in Beijing's Western Hills. When Zhu Zaihou ascended the throne in 1567 he gave her the title of empress posthumously. Her coffin was transferred to Zhaoling in 1572 and reburied with the emperor.

Empress Xiaoan

Empress Xiaoan (family name Chen) was also a native of Beijing, born to father Chen Jingxing, Count of Gu'an, but mother unknown and no birth year recorded.

She was chosen as concubine to the prince in 1558 upon the death of Empress Li. She became Empress in 1567 but fell in disfavor with the emperor already in 1569 and moved to a minor palace. As reason, the emperor claimed she was prone to illness and was infertile but allegedly he was angry about her critizing his overindulgence with music and women.

She did not receive proper care and although always respected by the crown prince and later Wanli Emperor she lived out her life in misery and passed away in 1596. However, the Wanli Emperor upon ascending the throne in 1572 bestowed her the honor of Empress Dowager.

Empress Dowager

Xiao Ding

Empress Dowager Xiao Ding (family name Li) was born 1546 in Beijing to father Li Wei, a pauper. After she gave birth to the Heir Apparent her father and mother were ennobled to Duke Zhuangjian of An and Lady Wang, Countess of Wuqing, respectively.

She was at first a simple court lady in the prince's palace from 1560. When the prince ascended the throne in 1567 he bestowed upon her the title of imperial concubine of the highest rank ("Noble Consort"). Her name was concubine Lishi.

She gave birth to several sons, among them in 1563 Zhu Yizhun, who in 1573 became the Wanli Emperor. In 1596 the emperor bestowed her the title of Empress Dowager after the death of Empress Xiaoan.

Empress Dowager Xiao Ding died 70 years old in 1614, an unusual high age at that time. Other than being the mother of the next emperor, she also contributed positively to China's history through a calming and benevolent influence on the first years of her son's reign.