Zhu Yizhun - the Wanli Emperor

Zhang Zhuzheng inspects offloading of corn

A Futile Reign

Zhu Yizhun was born September 4, 1563 as the third son of the Longqing emperor, who died in 1572. Being his eldest surviving son, Zhu Yizhun ascended the throne 9 years old as the Wanli emperor and the 13th emperor of the Ming dynasty.

He reigned for 47 years, the longest of any Chinese emperor since the Han dynasty in 2nd Century BC. Well, "reigned" maybe a stretch since he took so little interest in state affairs that it might be more fair merely to say that he was emperor for 47 years.

Gold crown

Like his father he indulged himself in a life of luxury and extravagant spending of the empire's coffers. When he died on August 18, 1620 he left an administration in a state of complete paralysis and an empire on the brink of demise.

Poor Government but Great Economy

The empire transcended through a huge paradox in Wanli's 47 years on the throne. While on the one hand the government was horrific except for the first 10 years, the economy boomed and prosperity reached new higher levels.

Since Zhu Yizhun was only 10 when he became emperor in 1573 the empire was at first governed by the very able Grand Secretary Zhang Zhuzheng, who however passed away in 1582. Zhang implemented sweeping reforms, simplified the tax system, augmented silver as currency and brought the massive corruption under control. He took a personal interest in promoting good and honest labor and eschewed small talk.

Trade blossomed and with the import from abroad of new crops like sweet potatoes and maize food production increased significantly allowing a much faster growing population -reaching over 100 million. Production specialized and quality was improved further leading to a massive demand for Chinese goods and, eventually, to a new caste of wealthy businessmen, bankers and merchants.

All Good Things Come to an End

Hat worn by Zhu

Yizhun in his coffin

But whereas the economy prospered under Zhang's hand, the Wanli emperor withdrew further and further from state affairs. He eventually completely neglected his public duties and didn't even attend the funeral of his own mother.

When Zhang passed away the entire government came to a standstill and remained in this paralysis for over a quarter of a century. The brief upswing under Zhang was soon wiped out and the eunuchs now had a field day in usurping the country.

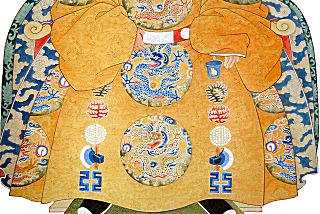

The emperor himself was spending lavishly -not just on himself but also on palaces and tombs. His tomb - Dingling - is the most elaborate of all Ming emperor tombs. In his last years he was so fat that he needed assistance just to stand up.

Towards the end of Zhu Yizhun's reign there was a general feeling of despair and frustration amongst the ministers and the population at large. People started taking to banditry and even outright rebellion. The stage was set for the final chapters and curtains for the Ming dynasty.

The End Is Approaching

Ming is defeated at Shenyang

The Ming army was inefficient and had a hard time dealing with the many incursions: The Mongols invaded from the north, minorities rebelled in the Southwest and Japan invaded Korea.

But while the Ming troops were busy coping with all of these as well as internal rebellions a far more dangerous enemy was approaching from the northeast.

Manchu leader Nu'erhachi had in the early 1600's organized all Manchurian tribes into a fierce fighting force in a so-called banner system. By the early 1620's his fighters had seized Manchuria all the way down to the area around today's Shenyang.

Ming failed to realize the huge exposure and treated the Manchurians more as a nuisance than a real threat. This mistake would soon cost them dearly: The overthrow of their dynasty.

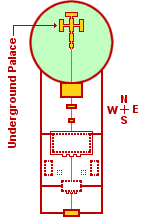

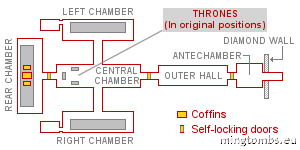

Dingling layout

Dingling basically follows the design of Changling.

It has a separate front gate so that the main gate actually lies inside the front gate.

The main gate is now just ruins apart from the stone platform. The same goes for the main sacrificial hall, Ling'endian.

The east and west side halls as well as the traditional silk burners were destroyed in the 1640's and have never been rebuilt.

There is no gate dividing the sacrificial and burial areas as the dividing wall connects up to Ling'endian itself.

The burial chambers have been excavated and is a favorite tourist attraction.

There are a total of five halls in the underground palace. A front and central hall, two side halls for concubines and the main hall in the back for the emperor and his empresses.

The mausoleum is open to the general public and well worth a visit but primarily to explore the underground palace. The ground structure are better in other tombs.

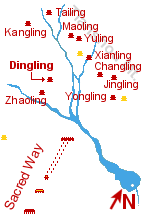

Tomb location:

Google Earth:

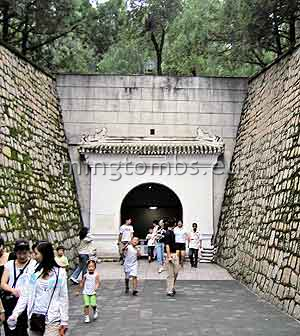

Front gate of Dingling at the foot of Mt. Dayu

Lavish Size

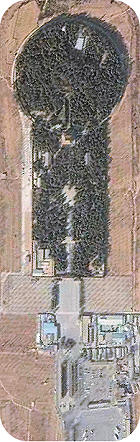

Zhu Yizhun was buried in Dingling, located at the eastern foot of Mt. Dayu and a few kilometers south of Changling, the first Ming tomb around Mt. Tianshou.

The Wanli emperor wanted to make sure that his tomb would be exceptionally ostentatious so he commenced building his mausoleum relatively early in his reign. Construction started in November 1584, his 12th year as emperor, and was completed in June 1590. He died and was entombed in 1620. The tomb cost a whooping 80 million tales of silver!

Covering an area of some 180,000 square meters Dingling is one of the largest tombs of the Ming mausoleum area.

Bridge in front of Dingling

Dingling is the only Ming Emperor tomb ever to be excavated so far. It had never been robbed so it contained a treasure trove of magnificent ancient articles.

Outside the Courtyards

But back to the beginning. Dingling was originally equipped with an outer wall surrounding the entire tomb and tomb wall. Little remains of this outer wall today.

The first structure that greets the visitor is the outside bridge spanning a small river running in front of the mausoleum. The river ensures to contain “qi” within the area.

Memorial stele

The bridge has three one-arch spans with the center span being larger than its sisters and for the exclusive use of the emperor.

Gargoyle at Ling'enmen

The inner Sacred Road runs straight from the bridge up to a square platform with the stele of merit in its center. The stele was originally housed in a square building with a double-eave roof, but the structure was destroyed in the early part of the Qing dynasty and never restored.

The stele is carried on the back of the traditional tortoise shaped animal and is surrounding by a small wall. Visitors find the stele irresistible and simply must have their photo taken standing in front of it with their kids, girlfriend or family.

As customary for Ming mausolea the stele carries no inscription and is decorated at the top with dragons playing with a pearl.

A little north of the stele is the point where the southern part of the original additional outer wall ran east-west. The wall surrounded the entire mausoleum, but only remnants of its foundation can now be found here and there.

Dingling front gate -note the larger center opening

Some 100 meters further ahead (north) on the inner Sacred Way is a large platform, at the other end of which lies today’s front gate. Dingling is one of the only three Shisanling Ming tombs, which can boast three courtyards, so this gate only gives access to the first courtyard. The other triple-courtyard tombs are the Chang Ling and the Yong Ling.

If photography is your thing then this is where you take a picture of the front gate looking straight north. On a clear day your photo will capture Mount Dayu towering behind Dingling. Any closer and the mountain will be covered by the gate.

Front Gate

The front gate is a relatively simple, five bays wide and three bays deep, solid construction. With only three evenly spaced openings it yields an impression of being both massive and imposing, likely intended since it protects a mausoleum from intruders.

Inner Sacred Way and Ruins of Ling'enmen

It is painted in vermilion color and has a single eave hip and gable roof with yellow glazed tiles (photo above). The three openings are arched and have wooden doors. On both sides of the gate the extant outer wall topped with yellow glazed tiles stretches east and west.

Gate of Heavenly Favors

Inside the front courtyard the inner Sacred Way runs straight for some 80 meters flanked by an extra line of stones until it meets up with the platform for the sacrificial gate, Lingen’men or Gate of Heavenly Favors.

The gate was originally 26.5 meters wide and 11.5 meters deep. Judging from the remaining plinths it was three bays wide and two deep. It was equipped with a single-eave, hip and gable roof.

Ling'enmen - plinths

The building was burned down during the 1644 uprising, which saw the overthrow of the Ming dynasty in favor of the Qing dynasty. The Qing Qianlong emperor had a reduced scale version re-erected in 1787 but also this was seriously damaged during the Republic of China (1912-1949). Eventually the debris was cleared and now only the platform and the plinths remain.

Balustrade details:

Dragon and phoenix

The platform has a triple staircase on the northern and southern side. In order to preserve the original stairs, the stone steps have been covered by a metal cover.

The wall which separates the front court and the middle court has been extended all the way up to where the sides of the original building would have stood. A simple passageway can be found in the eastern- and western side of this wall.

The middle courtyard does not contain any structures and having been paved over no remnants of any buildings can be found on the ground.

South side of Lingendian platform

Hall of Heavenly Favors

The Inner Sacred Way continues down the center up to the platform on which the main sacrificial hall, Ling'endian was originally built.

The large platform is elevated almost two meters. It has been cleared of all the original structures leaving only the foundation of the sacrificial hall and its plinths.

It has three staircases on the southern side and one each on the eastern and western side. It has a single staircase on the northern side.

Slab in the south center staircase at Ling'endian

New balustrades have been built alongside all the staircases and edges. The decoration of the pillars carry the traditional dragon ("emperor") or phoenix ("empress") winding itself around the top.

Northern slab

The traditional stone slab can be found in the middle of the center stairs on the northern- and southern side (photo). It displays the usual water and mountains at the base above which a dragon and a phoenix are playing with a pearl in the whirling clouds. The slabs appear new or restored.

The main hall was built in 1585 and was originally an impressive 7 by 5-room ("jian") structure with a double-eave, hip and gable roof covered with yellow glazed tiles.

The hall was used to keep tablets, scriptures and personal effects of the emperor and empress. The worship ceremonies were also held in this hall.

Ling'endian platform -note the reduced hall size

Like Ling'enmen gate, the hall was seriously damaged in the mid- and late 1640's. When the Qing Qianlong emperor had it restored in the late 1780's it was reduced to a more humble 5 by 3-room structure.

The photo clearly shows how the remains of the hall itself is dwarfed compared to the size of the platform.

The walls separating the middle and the back (north) courtyards have been built all the way to the eastern- and western side walls of the sacrificial hall. As in the sister walls at the gate there are two simple passageways in the wall on both sides of the platform.

- Lingxingmen -

Double Pillar Gate

The Back Courtyard

The back courtyard contains the usual Double-Pillar gate -Lingxingmen- and the five sacrificial stone vessels.

Sacrificial stone vessels

Lingxingmen has been fully restored to past splendor (photo); the kylins tower on top of their respective uprights, the wooden doors are in place, the crossbeams are magnificently painted and the yellow glazed roof tiles glitter in the bright sun.

The five sacrificial stone vessels in front of the soul tower have been restored and put back on their finely decorated stone altar.

Soul tower with stele and side ramp

The soul tower also stands magnificently restored. The stele inside carries the inscriptions "The mausoleum of emperor Shenzong" and "Da Ming" (Great Ming). Shenzong was Zhu Yizhun's temple name and means "Spiritual Ancestor".

The Square City, the huge, solid platform on which the Soul Tower is erected, does not have an opening in front and a tunnel through its center as found in most Ming tombs.

The crenellated walkway

Instead stairways or ramps on both sides of the Square City lead up to the crenellated walkway surrounding the tomb mound -and from the walkway again up to the Soul Tower (photo).

Dingling does not have a "Mute's Yard" between the Square City and the tomb mound. This area is now occupied by a path that leads back up from the Underground Palace.

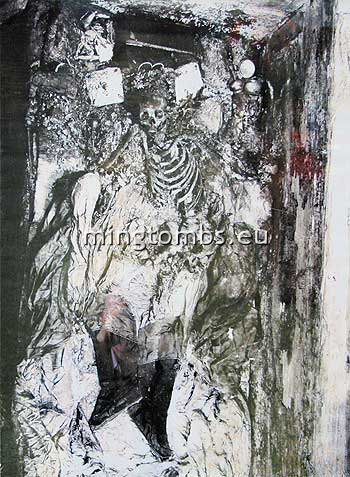

A more recent addition to the back courtyard are two low, rectangular buildings sitting alongside the east and west wall, respectively. These buildings are local museums housing pictures and artifacts from the excavation of Dingling mausoleum.

Exit from the underground palace

These museums are well worth a visit. They contain for instance pictures of the first opening of the tomb, the coffins of the emperor and empresses sitting untouched on their platforms, the Wanli emperor in his coffin and many more. Also exhibited is the incredible original direction tablet found during the excavation (see insert).

Underground Palace

This is where we leave this earth and journey to the netherworld. Above all it's the Underground Palace of Dingling that draws the crowds. And righteously so.

Old outer wall

Commencing just left (west) of the Soul Tower is a path that will wind peacefully between the old trees planted on the tomb mound. The path ends at the northern end of the mausoleum where the official entrance to the excavated Underground Palace is located.

While there take a look directly north from the walkway. Just behind the round outer tomb wall there are some dilapidated bricked wall sections which are likely part of the original additional surrounding mausoleum wall. This is the only place that I could find any part of this additional wall.

One descends a long series of stairs going deep down below the ground surface until finally arriving at the back end of one of the underground side chambers.

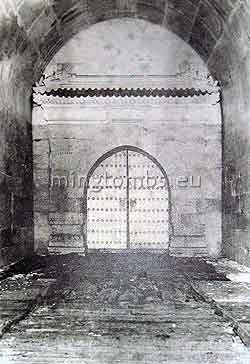

Diamond wall entrance

But before entering the tomb let's first go back to 1956 when the idea of the excavation was first conceived.

Direction Tablet

In September 1956 during the digging of one of the early probing ditches, the excavators uncovered a small stone tablet.

It was engraved down the center with 16 Chinese characters literally meaning, "from this stone to the front of the Diamond Wall, it is 16 zhang long and 3 zhang and 5 chi deep".

The Diamond Wall was the entrance to the Underground Palace.

Indeed, when the excavators finally reached the tomb entrance it was confirmed to be exactly 52.8 meters horizontally and 11.5 meters vertically from where the tablet was found (1 zhang = 3.3m, 1 chi = 0.3m) !!

The picture shows the original Direction Tablet. It is on display in Exhibition Hall No.1 inside Dingling tomb, but there is unfortunately no signage explaining how important this inconspicuous piece of rock was.

The Excavation 1956-58

In May 1956 the State Council gave its permission to commence excavation of -no, not Dingling- but Changling. The archaeologists however wished to make a trial excavation of Dingling first so as to use the experience gained on Changling. That was probably a good decision since it took one year before they finally even found the front gate to the underground palace.

The excavators decided to commence the digging in an area to the right of the Soul Tower because part of the wall outside of the Bao Cheng had collapsed indicating a possible weakness.

They indeed discovered the tunnel gate at that location and a subsequent larger ditch uncovered a brick tunnel and a stone engraved with the Chinese words meaning "The Tunnel Gate" on the Bao Cheng wall.

Locked marble doors

Spurred on by the success they dug a couple of larger ditches and soon found a small stone tablet giving the exact measurements from the stone to the front entrance of the Underground Tomb (see insert). This tablet has later been nicknamed the "Direction Tablet".

After emptying the stone tunnel of soil they reached the so-called "Diamond Wall", the front entrance of the tomb chambers. The photo on this page shows the opening today and (inserted in left hand corner) what it looked like just before being breached. The A-shape of the Diamond Wall imitates the Chinese character for person ("Ren").

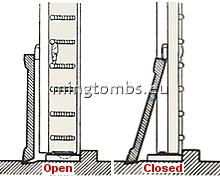

Self-locking mechanism

Passing through the Diamond Wall the archaeologists found themselves in an eerily quiet but empty antechamber. At the far end were two massive marble doors. The doors replicated the imperial doors in The Forbidden city, complete with nine rows and nine columns of nails -in marble of course. The doors were locked but with no obvious locking mechanism.

Thrones in central hall

After some investigation they uncovered that the doors used an internal self-locking system. A beveled marble pole had been placed on the inside in a groove in the floor leaning against the almost closed door. When the door was pulled shut the pole would slide under a small protruding bar on the backside of the door making it impossible to push open the door again from the outside (see drawing).

Wanli's skeleton as found in 1957

It took the excavators a while to figure out how to open these doors without damaging them. In the end they used a fixed wire frame and pushed the locking pole away from the door.

They applied the same method on the other self-locking doors (see plan) eventually gaining access to all the underground chambers.

Once this hindrance had been overcome the entire world was enriched with an incredible treasure of ancient relics especially since it turned out that the tomb never had been robbed.

Five Chambers

Behind the diamond wall was a small antechamber followed by an outer hall. Both of these chambers were empty.

Plan of the underground tomb

Behind the outer hall and still on the center axis was the central hall, a six meter wide and thirty two meter deep corridor with connections to the remaining three chambers.

The central hall housed three large stone thrones, one for an empress on each side of the one for the emperor. Various ritual vessels and a large, blue/white porcelain vase was placed in front of each throne.

The thrones have been moved from their original location and instead lined up behind each other in the center of the central hall.

Side hall for concubines

Gold Well in the center

The porcelain vases were filled with sesame oil and a wick, intended to provide everlasting light for the tomb occupants. But the light had died out soon after the chambers were sealed due to lack of oxygen.

Passageway

Parallel to and flanking the central hall were two side chambers. These two chambers were intended for those of emperor Wanli's concubines, who outlived him. Obviously it had been considered unlucky to reopen the tomb after the burial of the emperor and the empresses in 1620 because both side chambers had no coffins.

In each side chamber as in the main chamber was a stone platform framed with white marble. The coffins were placed on top of the platforms. In the center of these stone slabs was a small, square hole filled with loess linking the coffin with the ground; the hole is known as the "Gold Well".

Coffins of the emperor and empresses (replica)

The back chamber and main hall of the underground palace held the coffins of the Wanli emperor and empresses Xiaodian and Xiaojing, aka. empresses Wang. Placed around the three coffins were another twenty six red lacquered chests of nanmu wood filled with sacrificial objects and jade pieces.

The coffins now on display are copies of the original ones, which had decayed and are kept at another location.

The entire layout is an imitation of The Forbidden City with the outer hall, central hall and main chamber respectively being Qianqinggong (Palace of Heavenly Purity), Jiaotaidian (Hall of Union and Piece) and Kunninggong (Palace of Terrestrial Tranquility). Left and right side chambers would correspond to Dongliugong (Six Eastern Palaces) and Xiliugong (Six Western Palaces).

Tomb Occupants

The occupants of this underground palace were fortunately left to their eternal rest while the topside structures of their mausoleum were ravaged by rebels already within 20-25 years of the passing of the emperor.

The Wanli Emperor was laid to rest between his two wives, Empress Xiaoduan and Empress Dowager Xiaojing, both surnamed Wang.

Empress Xiaoduan (left), personal name Wang Xijie, was a native of Zhejiang Province. She was born 1564 to father Wang Wei, Count of Yongnian, but the mother's name is unrecorded.

She entered the palace harem in 1577 and became Empress and first wife of the Wanli Emperor already in 1578, just 13 years old. She had no sons and died of illness in 1620, the same year as the emperor passed away. Also in that year, she was posthumuously honored with the title of Empress Xiaoduan.

Lady Wang, formally Empress Dowager Xiaojing (right), was born 27 February 1565 to father Wang Chaocai, Count of Yongning, and mother Lady Ge, Countess of Yongning.

She entered the imperial harem in 1578 as a simple palace lady, but was promoted to Respectful Consort in 1582, when she became pregnant with Zhu Changlou, the later Taichang Emperor. In spite of pressure by Empress Dowager Xiaoding for her son to marry Wang, he refused as he preferred to name as heir apparant the son of his favorire concubine, Noble Consort Zheng. Only in 1601 did the emperor finally name Lady Wang's son as heir apparent.

In 1606 she was bestowed the title of Imperial Noble Consort, the highest rank just below Empress.

She died in 18 October 1611 of illness and was buried in Tianshou Hill. When her grandson, the Tianqi Emperor, succeeded to the throne in 1620 he bestowed her the posthumous title of Empress Dowager Xiaojing and had her exhumed and reburied with the Wanli emperor in Dingling.